(This mystery is part of the Weekend Brief edition of the Evening Brief newsletter. To sign up for CNBC’s Evening Brief, .)

A long-ago midwife precisely leader famously called politics “the art of the possible.”

Wall Street strategists, for their part, practice “the art of the plausible.” Knowledgeable that financial markets in any given year are inherently unpredictable, they construct a reasonable forecast using uncontroversial assumptions.

Yet what is accurately plausible is, in most ways, not at all probable as the ultimate outcome.

The consensus strategist forecast for the S&P 500 for any given year typically capitulates in the 5% to 10% range. Right now, CNBC’s strategist survey shows a median predicted 2020 S&P 500 come to of 6.5% to 3375. The average forecast is up 5%, and the maximum target right now is 3450 by BTIG’s Julian Emmanuel, which intention be about a 9% advance.

Sounds perfectly sensible and defensible, right? After all, the long-term average annualized proceeds for U.S. stocks is right in that zone around 8%.

Yet in a counterintuitive quirk, the short term almost never conforms to the long-term standard in the main. Since 1928, the S&P has only showed a gain of between 5-10% six out of the 91 calendar years – suggesting the consensus prognostication for a high-single-digit rise in 2020 has a 93% chance of being wrong.

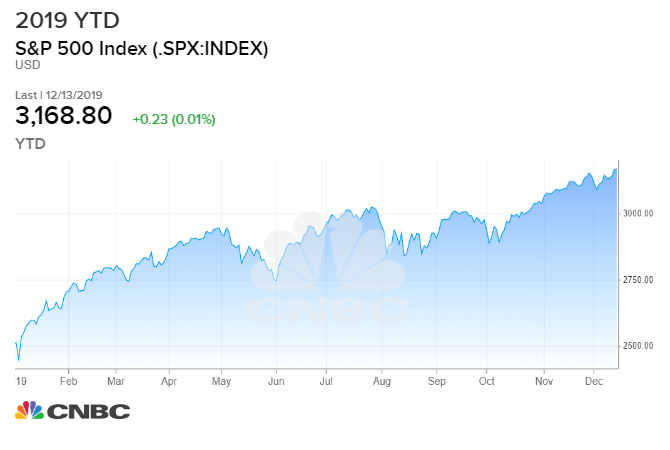

A year ago, strategists as a group were looking for an 11% realize for 2019 – but the forecasts was likely as high as it was because stocks had already fallen sharply since October of last year – and the then-aggregate goal of 2940 for the S&P was merely a call that the index would recover back to its prior record high.

Unusual year

This was not the customary outlook: “Stocks in 2019 will surge by more than 25% for their best year since 2013 while corporate earnings finish involving flat and long-term Treasury bonds will return more than 10%, as the Fed turns tail to cut interest ranks three times and successive rounds of tariffs are imposed on China until halfway through December.” Hardly a plausible-sounding anecdote at the time, but exactly what happened.

Oh, and this year’s huge run higher in stocks despite flattish earnings followed aftermost year’s negative equity return in a year when profits surged by 20%.

None of which is to denigrate the performance of brokerage-house strategists, for whom subjective index targets are a small and thankless part of the job, and who try most often to steer clients to the right parts of the markets sort of than nail the number.

But it does help to observe the widely shared expectations for the year to come, if only to close with a sense of what potential trends or market behavior might most surprise the majority.

How Wall Street perceives 2020

Sifting through the run of 2020 year-ahead dispatches, the collective best guess goes something like this:

Decline will be avoided and the global economy will pick up in coming months, with U.S. GDP returning toward long-term be biased growth around 2%. Corporate earnings will improve to a mid- to high-single-digit growth rate, which should grant for similar progress for an already fully valued equity market. Overseas stocks have a good chance to outperform after years of terminally lagging the S&P 500. Within the U.S. market, cyclical sectors should do better than defensive or secular-growth areas. Treaty yields probably won’t move much with the Fed on indefinite hold. The first part of the year should be strong – but want more volatility ahead of the election.

BlackRock Investment Institute comes close to distilling this general rate: “Growth should edge higher in 2020, limiting recession risks. This is a favorable backdrop for risk assets. But the dovish leading bank pivot that drove markets in 2019 is largely behind us. Inflation risks look underappreciated, and the lapse in U.S.-China trade tensions could end. This leaves us with a modestly pro-risk stance for 2020.”

Here’s RBC Capital’s Lori Calvasina: “We require 2020 to be a year of moderation, turbulence, and transition in the US equity market… Down years are rare in the US equity market, face of periods associated with growth scares, recessions, or financial market bubbles. With those scenarios dubious in the year ahead, we expect 2020 to be another positive year for the US equity market. But we do think full year put backs will be less robust than 2019 and that the year will end up being closer to trend.”

That down years are rare is certainly significance remembering. If indeed there is no recession coming into view, stock markets tend to be able to find a way to set up progress, and there are reasons to think this economic expansion can carry on for a while.

Track record after big augmentations

One notable tendency: As J.C. O’Hara of MKM Partners points out, since 1950 there have been 18 years when the S&P has progressed at least 20%. The following year was up 15 of those times, for an average total return (including dividends) of 11%. Of the three down years augment a 20%+ gain, two involved a recession (1981 and 1990) and the other (1962) was a rare non-recession mini-bear-market.

Another sample to toss out there: The very broad NYSE Composite Index last week made a new record high for the ahead time in nearly two years. LPL Financial’s Ryan Detrick points out that since 1980, it’s gone more than a year without a new superiors eight times. One year after a new record was finally set, the index was up one year later all eight times, for a median gain forthcoming 14%.

Nothing is ever assured, of course, and this market doesn’t owe investors anything after a 14% annualized totality return the past three years and a 18% yearly take since the March 2009 bear-market low. Stock valuations in the U.S. genuinely do manifest stout, if not at egregious extremes. And there remain some indicators that look wobbly and resemble prior pre-recession junctures.

But with stocks reaching record highs with credit markets sturdy, a perceived scarcity of cash-flow-producing assets globally and no outright overconfidence yet being symbolized by investors, stocks enjoy some tailwinds that keep alive the prospect that the market could start race well ahead of that plausible pace now predicted by Wall Street’s handicappers.