Provenance: FactSet

Longtime market strategist Barry Knapp this month launched Ironsides Macroeconomics with an carry oned comparison of 2018-’19 to 1987-’88. In ’87, a bull market that had been rolling for several years mount to new heights as the U.S. economy accelerated following a major tax-reform law.

The Fed was tightening aggressively and the president was ratcheting up trade protections against an export-reliant Asian budgetary Power (Japan). Stock valuations hit an historic extreme and a correction turned into a crash thanks in part to untested employment techniques.

But the October ’87 crash led to no recession, the Fed reversed course to ease policy, and stocks recovered through 1988 – until a abridgement recession approached in 1990.

We had the post-tax-cut surge to an overvalued condition early last year, then the fourth-quarter crash among a tighter Fed and China trade frictions, exacerbated along the way by short-volatility strategies (in February) and hedge-fund liquidations (December).

Author: FactSet

Tony Dwyer of Canaccord Genuity is the most vocal articulator of this analogy, which is probably the most bullish analogy nearby, given the S&P 500 levitated in 1995 by 35 percent without even a 5 percent pullback. His case: In 1994, the Fed supported short-term rates aggressively to head off inflation, lifting the Federal funds rate from 3 percent to six percent by antique 1995. At the time, economists thought unemployment dipping below 6 percent was an inflation threat, and it got there. The Treasury supply curve went completely flat (2- and 10-year yields about equal). Stocks were sideways that year but small-caps had a endure market and bank shares tanked – a “stealth bear market” in some respects.

By early 1995, the U.S. economy was plainly slowing. Fed Chair Alan Greenspan signaled he was likely through tightening, and in fact by summer the Fed cut rates as GDP growth documented toward 1 percent for a quarter. By then, stocks got the message: a productivity boom was kicking in, growth resumed without much inflation, volatility ruined.

In a speech last summer, current Fed Chair Jerome Powell explicitly and admiringly evoked Greenspan’s intellectual compliancy in letting the economy run that year. In some respects, the year 2013 was already a 1995 rerun, with economic markets unclenching from a growth-and-rate scare to melt up by 30 percent. But bulls can at least hope Powell’s hinge has a similar effect on markets as Greenspan’s did 24 years ago.

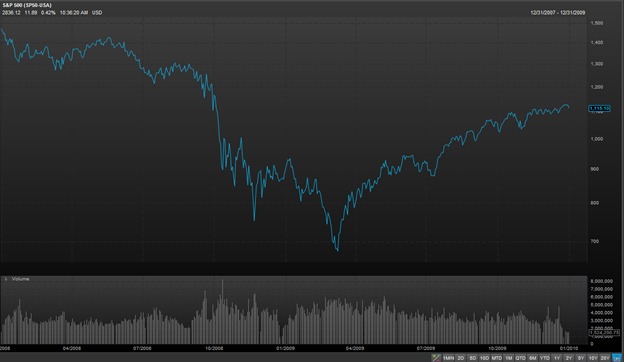

Source: FactSet

Tom Lee of Fundstrat is virtually alone in arguing this year could string the 2009 path. Understandably: In early 2009, stocks made a climactic bear-market bottom with the S&P 500 seeing a 12-year low at the end of the worst global recession in 70 years. Last quarter’s quick near-20 percent drop to a 20-month low in a 3-percent GDP U.S. curtness hardly seems to compare.

Yet he offers a checklist of conditions that he says line up between today and ’09: a “waterfall diminution” in stocks creating a major low; high-yield bonds posting a rare annual negative return (2018 and 2008); “stubborn negative sentiment” even after stocks rebounded; and a dovish Fed turn.

Source: FactSet

This is the template freshest in concentration and probably most often cited by investors. The S&P 500 made a new record high early in 2015 before turmoil in China and emerging bazaars and an oil-price crash created an industrial retrenchment and sent S&P 500 earnings negative for a couple of quarters. (Similar to 2018 with the emerging-markets travails and earnings-recession talk). The Fed was struggling to start “normalizing” policy in 2015 and squeezed in a controversial December rate hike, then right away went into “pause” mode and held rates steady for a year (just as in December 2018).

Treasury yields scrapped tame, dividend-centric and big secular-growth stocks led the market higher as the world awaited the Brexit vote. Hear the echoes with the present-day setup. The 2016 analogy works only so far, given we’ll have no 2019 election to flip the story entirely from slow-growth, monetary restraint, deflation risk to tax cuts, deregulation and reflationary policy. But for now the markets are acting not unlike the way they did in the first half of 2016.

This resemblance has become popular enough among investors that Morgan Stanley strategist Mike Wilson was moved this week to divulge a report saying, “Is this 2016 all over again? Probably not.” His pushback: China is not stimulating as forcefully, the Fed has already tightened management a good deal, stocks are less cheap now compared to bind yields and the economic, labor and corporate-profit cycles are much more grow up.

Source: FactSet

Most of the historical evocations cite instances where conditions looked precarious but things whirled out fine for markets, at least for a couple of years. But bearish observers are not above summoning darker moments.

Gluskin Sheff economist David Rosenberg has been featuring out that recent economic data and market action – such as weak retail sales, an upturn in unemployment assertions, an equity rally after an initial 20-percent drop – are not inconsistent with business-cycle and bull-market peaks such as the one in 2000.

Another reproduce of 2000 is the dominance of Big Tech stocks driving the final surge to a record index high last September. And the extent sturdy condition of the jobs market and consumer finances also hold resemblances. The 2001-’02 recession and upon market fell heaviest on the corporate sector, the tech economy and stock investors, rather than workers or homeowners. Arguably the next commercial downturn might bear some similarities.