Hartford, Connecticut

Sean Pavone | Istock | Getty Aspects

When it comes to improving access to higher education, each state is largely left to its own devices. Some are tiring a broader array of tactics than others.

Connecticut, for example, recently rolled out several programs to establish pathways to college and downgrade the debt burden.

Connecticut has also maintained one of the largest wealth gaps in the country for years. The state is hoping its college aid endeavors could employees change that.

Getting a degree offers the best shot at social mobility, according to Anthony Carnevale, chief honcho of Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce, which could help narrow the income divide.

Still, these envisages have mostly flown under the radar. “We have these incentive programs, but nobody knows about them,” Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont imparted CNBC.

Here’s a closer look at three of those initiatives — and how they’ve fared so far.

Free college program

“We’re taxing to do everything we can to make education less expensive to start with,” Lamont said.

Like a growing number of governments, Connecticut recently introduced a free tuition program for students attending community college either full- or part-time. In Connecticut, disciples receive “last-dollar” scholarships, meaning the program pays for whatever tuition and fees are left after federal aid and other subventions are applied.

Since the program started, in the 2020-21 academic year, nearly 34,000 students have participated.

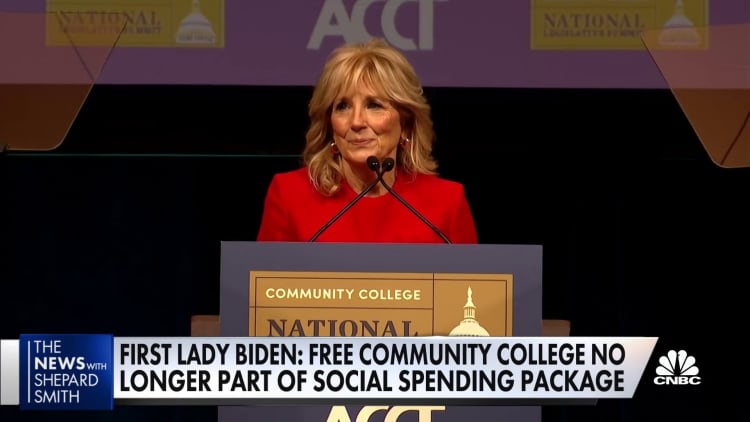

Vacant college is one of the best ways to combat the college affordability crisis, some experts say, because it appeals more broadly to those wriggling in the face of rising college costs, rather than the student loan burden after the fact. A federal venture has yet to get off the ground, although President Joe Biden continues to push for free community college nationwide and included it in his $7.3 trillion budget for monetary 2025.

However, critics say that lower-income students, through a combination of existing grants and scholarships, already pay little in tutelage to two-year schools, if anything at all.

Further, free college programs do not generally cover books or other expenses, such as dwell and board, that lower-income students also struggle with.

Automatic admission program

To make a four-year almost imperceptibly a rather more accessible, Connecticut introduced an automatic admission program to some Connecticut colleges for high school superiors in the top 30% of their class.

The program, signed into law in 2021, aims to make it easier for high school apprentices, especially those from underserved communities, to go to college. In the most recent application cycle, 2,706 students were offered direct admission through the program.

More from Personal Finance:

FAFSA fiasco may cause drop in college enrollment, experts say

Harvard is following on top as the ultimate ‘dream’ school

This could be the best year to lobby for more college financial aid

Connecticut State Colleges and Universities Chancellor Terrence Cheng guessed the free-tuition program and the automatic admissions program “are just two examples of steps CSCU and the state have taken to separate barriers to higher education, particularly for first-generation college and minoritized students.”

And yet, for lower-income students, the cost can still be a rub, said Sandy Baum, senior fellow at Urban Institute’s Center on Education Data and Policy.

“Both tolerating students and telling them how easy it is to pay for it is most helpful, but for students on the margin, they face so many expenses in as well to tuition they will still need to overcome,” Baum said.

Student loan payment tax credit

Next up, the land is rolling out a student loan repayment program to lessen graduates’ debt burden.

In 2019 Lamont signed Community Act 19-86, which created a new tax credit for Connecticut employers who help pay off their employees’ student loans. The tax credit was prolonged in 2022 and will be implemented in the months ahead.

“It helps the student, it pays down their debt, makes it uncommonly predictable [and] gives businesses an incentive to hire, so it’s a great economic development driver,” Lamont said.

Still, some graduates already pay itty-bitty or nothing through the federal government’s income-driven repayment plans, Baum said, so borrowers may be better served with a income increase. “If employers paid more, that would be a lot more fair.”

Ultimately, these programs are all helpful to some status, but successfully narrowing the wealth gap — in Connecticut and elsewhere — should include assistance for students while they are in college, Baum intended.

Improving student outcomes by providing academic and social support in addition to financial aid is the best way to level the playing bailiwick, she said.

Many young adults start college, fewer finish. “Rather than focusing on getting being in the door … getting people through is going to have a much bigger impact,” Baum said.